Gallery of Curiosity

This page is dedicated to all the fun observations I’ve made prompted by curiosity. As you scroll through, you’ll find plenty of silly observations, some delightful discoveries, and maybe even a few intriguing ones that remain a mystery to me. You might also come across images from experiments that never made it into a publication, quirky snapshots, mesmerizing microscopic worlds, and other small moments that sparked joy. I think of this page as my “gallery of curiosity”, filled with the things that made me smile that might have otherwise gone unseen.

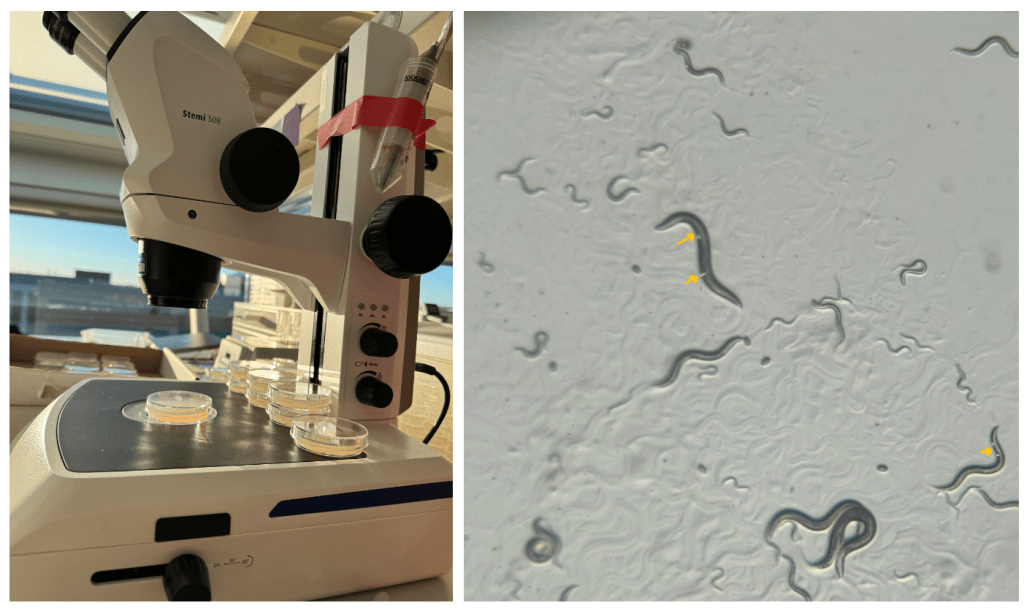

Sparkling worms.

The other worm lab at VAI showed us sparkling worms. I asked Jason why they sparkle (indicated by the yellow arrows), and, knowing him, he made up a story about a special strain. We later realized that the orientation of the window and microscopes is such that, at certain times, sunlight hits the bacteria around the moving worms, making them appear to shine.

So now, on most sunny days, somewhere around 5 PM, we make our worms sparkle, because they’re awesome.

Can your worms shine?

Spiders can be used to study aging.

This picture is memorable to me because I heard Andrew Gordus speak at the training course at MBL about developing spiders as a behavioral model for aging. I found his talk incredibly inspiring and infectious. So much so that I captured a spider and held it in a flat Petri dish for some time to study changes in its web pattern as it aged.

This experience really inspired me to believe that if something genuinely sparks your curiosity, you should just go for it. Although nothing tangible came out of it and I’m not working on spiders at the moment, it was immensely fun to imagine the kinds of questions one could ask about spider aging.

An extra loving plate.

I work with C. elegans (worms) in my current research. One way we culture them in the lab is by placing them on agar plates that are seeded with a harmless bacterial lawn, which the worms then feast on.

I really like this picture because, while placing the worms on the plate, I noticed that the bacterial lawn was heart-shaped. A funny coincidence was that this happened at the start of the love month – February 1, 2025.

Sometimes, it’s these small, cute, and fun moments that bring a smile during research.

I found this particular art piece at the Art Prize exhibition in Grand Rapids, Michigan. I stared at it for two minutes, feeling deeply connected to it yet unable to explain why. Then it hit me, it was the Pillars of Creation (the Eagle Nebula), and I got goosebumps. It instantly reminded me of my love for astrophysics while growing up.

I don’t exactly remember the name of the artist, but I’m grateful to them for creating such a fascinating art piece.

I love it when people merge art and science, and I hope I get to do that a lot.

The Barnacular Monsters of MBL Stony Beach.

For the first time, I finally got a chance to see these voracious creatures. I had only heard about their tales in our ecology class while discussing parasitism, where these beasts would feed on blue whales and slowly bring these giants to their knees – or should I say, flippers.

The dead ones have a hole in the middle, while live barnacles keep their openings closed to prevent drying out. They reopen once the tide returns.

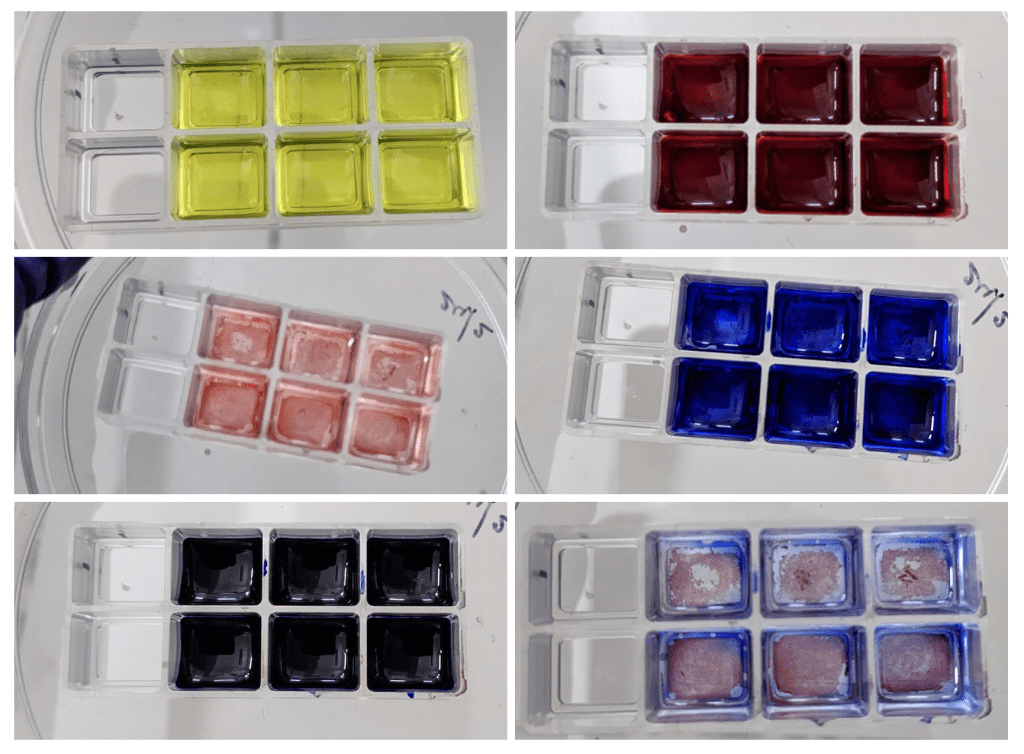

May all the colors be with me.

This remains one of the most colorful staining protocols I have ever performed. During my research in the Bhat Lab at IISc, I carried out Masson’s trichrome staining to visualize collagen in young and aged mesothelium and assess age-associated differences.

I no longer remember the exact results, and I don’t think the data ultimately made it into the final manuscript. What I vividly remember is the joy the process itself brought me – pipetting vividly colored solutions and watching tissues slowly transform at the bench.

In that moment, the inner child in me was happy.

Tardigrades rule the World and Space.

These are some images that I captured during the MBL aging course while working with Ryo, Aeowynn, Vinaya, and Jamie. They are scientifically less useful, yet aesthetically pleasing.

Top – Snapshot using lifetime imaging. I no longer remember the motivation for acquiring it, and the coloration is likely a depth-related effect. There is just something quietly captivating about it.

Bottom – Overexposed DAPI stain, entirely unusable from a data standpoint, yet, to me, undeniably beautiful. The claws, in particular, draw the eye. I do not know why they fluoresce with DAPI excitation wavelength; perhaps they’re made of keratin that absorbs UV?

Sometimes, experiments leave behind small visual gifts, moments of wonder that sit somewhere between biology and art.

Planarians – the most powerful regenerators.

This is a planarian, specifically Schmidtea mediterranea. Over the past few months, this has become one of my most fascinating creatures. They live in freshwater and are known for their incredible regenerative power. You can cut one into a hundred pieces, and each piece can grow into a complete new animal with all the missing organs.

This regenerative capacity is made possible by specialized stem cells called neoblasts. In fact, if you remove all the stem cells from a planarian and then inject just a single stem cell, that alone is enough to restore the animal and make it “immortal” again. There is so much to learn from these organisms, and I am deeply intrigued by their biology. I can’t wait to work with them in the future.

The image shows a planarian (left) and its dislodged pharynx (right).

The Starry Night.

I went to MoMA and saw Van Gogh’s The Starry Night. I still haven’t been able to put into words the kind of curiosity it ignites in me. I deeply love this piece, and I feel there is – or must be – some science behind how soothing it feels. Perhaps it’s the swirling, whirlpool-like brushstrokes, though I’m not entirely sure. Maybe someday, I’ll find some answers.

A scallop sees it all.

I had the opportunity to see scallops – these aquatic creatures are so bizarre and beautiful. They have so many eyes and can move through the water using just an abductor muscle. It’s unimaginable to me what these different eyes (~ 200 in number) see, and how the brain (or brain-like body) integrates all this information to make sense of its environment and respond accordingly. It’s truly impressive considering the small size of the animal and the low complexity of the nervous system compared to humans. Thanks to Indy for the narration.

Beware of the scallop, it’s always watching.

Suckers for SYMMETRY | YЯTƎMMYƧ

This picture captures some of the everyday, small, satisfying feelings you get as a researcher by simply looking at symmetrical things.

Left – Symmetrically organized column tubes while performing DNA isolation for 16 samples, carefully arranged to balance the centrifuge.

Right – Bacterial plates we use to feed worms. The lids often collect condensation because they are stored in a cold place, and this condensation can be surprisingly beautiful.

Mother C. elegans and her line of embryos.

This picture is a part of my memory lane. I took it at the start of my PhD, when I had just begun working with C. elegans.

This particular animal was one I injected with CRISPR mixes. It felt incredibly powerful – almost godlike, in the sense of being able to write DNA. I remember hoping that one of those embryos, arranged along a beautiful polynomial curve (red arrows), would develop into an animal I had created by changing its genome exactly as I wished.

The younger version of me would never have believed that I would one day do something like this. I remain deeply fascinated by such an exceptional model system. It continues to surprise me, again and again, with its elegansce.

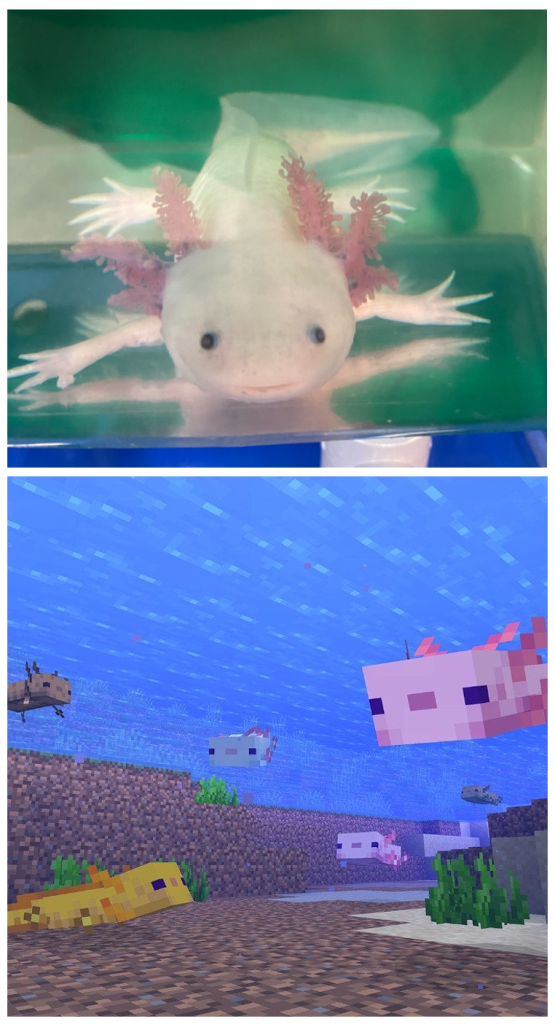

Virtually real axolotls.

In the Biology of Aging course, I finally got the opportunity to see a real axolotl – not an axolotl soft toy, not one in a research paper, not a sticker, and definitely not just axolotl memes, but a living, breathing axolotl!! Anyone who knows me knows how much I love axolotls; they are my absolute favorite animals.

One of the most surprising things I noticed was their behavior, how slowly they move, and how gently they respond to stimuli. It made me wonder how such calmness coexists with their extraordinary regenerative powers, or whether the two are somehow connected.

On a lighter note, I also learned that axolotls exist in Minecraft.

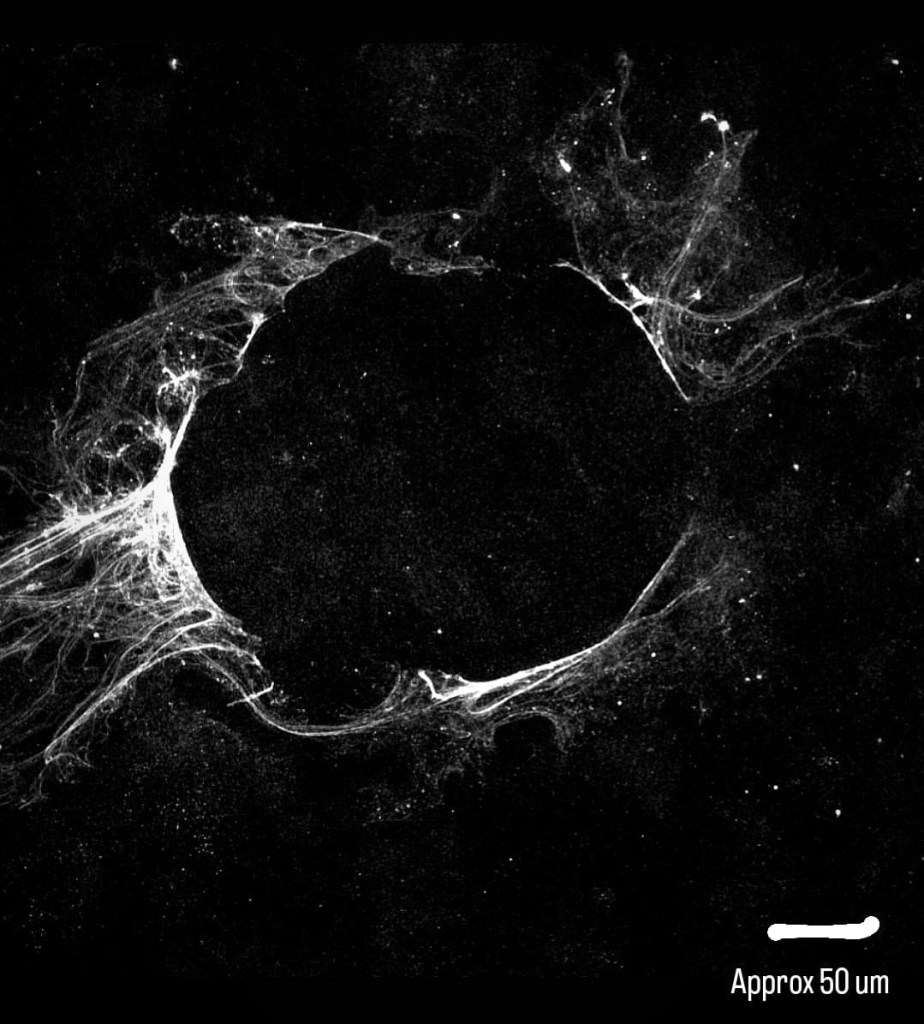

Tear in the Matrix of Life.

The first time I saw this image under the microscope, I had no idea what I was looking at. During my research in the Bhat Lab at IISc, I was seeding young and aged cells onto glass, allowing them to secrete their extracellular matrix (ECM). I would then permeabilize the cells and stain the ECM to probe how it changes with cellular aging.

Somewhere in those steps, amid pipetting and routine motions, I tore a hole in the matrix. The image, of course, became unusable for analysis. An artifact. A mistake. And yet, what struck me afterward was not the loss of data, but the presence of that absence. This is the mother matrix: the scaffold that holds our cells together, primes them, polarizes them, guides their behavior, and quietly dictates function and fate. Praise the matrix!

Rock N Roll Soniye*.

Presenting one of my favorite genetically modified C. elegans strains: the rollers. These worms are created by mutating dpy-10, a collagen gene essential for forming the cuticle – the outermost layer of the animal. The mutation leads to a smaller body size and may cause misorganized collagen fibers. As a result, instead of moving forward in a straight line, these worms roll. Hence the name.

Metaphorically, I love how carefree they seem, rolling in place, unconcerned with direction or destination.

So here’s your sign: be like a roller. Keep rolling through life.

(*The mystery behind the title is a Hindi song, linked here …)